A Deep Dive (Pun Intended) into Aquatic Milkweed Biogeography and its Implications for Monarchs

|

| Monarch Caterpillar Chomping on the Stems of Roadside Aquatic Milkweed |

Aquatic milkweed's evergreen habit and current distribution play a significant role in the lifecycle of monarch butterflies in the southeast, and raises questions about resident monarchs, migrating monarchs, and the great monarch migration itself. The following is (just about) everything one would need to know to understand where and why aquatic milkweed occurs where it does, and how this milkweed's habit AND habitat are important to monarch butterflies.

Regulatory Classification of Aquatic Milkweed

Asclepias perennis is classified by state and federal agencies as a wetland obligate (OBL) species. Regulating agencies utilize this species to aid in wetland delineations and determinations. Despite this regulatory classification, it is important to note that Asclepias perennis is not an obligate to wetland soils because of a biological requirement for hydric soils. Indeed, aquatic milkweed can be cultivated in mesic soils away from wetlands. However, Aquatic milkweed is an obligate to the greatly-reduced competition afforded by their ability to grow in saturated soils under closed canopies, often submerged underwater for portions of the year.

Essentially, if a wild population of aquatic milkweed is encountered, the population is probably within a jurisdictional wetland regulated by state and federal agencies. Aside from its wetland classification, aquatic milkweed does not hold any other sort of listing status; e.g. endangered, threatened, etc.

Aquatic Milkweed Habitats

There are primary and secondary habitats for Asclepias

perennis. A majority of populations and individuals occur in the species’

primary habitats. It is important to note that the species is versatile in

habitat utilization; thus, the species can occur within or at the edges of

virtually any wetland community type that occurs within drainage districts or

low-lying sheetflow platforms.

Primary

Natural Community Types

-

Rivers

and Streams - alluvial stream, blackwater stream, spring run

-

Forested

Wetlands - floodplain swamp, hydric hammock, coastal hydric hammock, alluvial

forest, basin swamp (in Big Bend and Southwest Florida), sloughs (in North

Florida and surrounding coastal plain)

-

Pine

Flatwoods - Wet Flatwoods

-

Sinkholes

and Outcrops - sinkholes (when connected by karst lens to disappearing

stream)

Secondary Natural Community Types

-

Forested

Wetlands - dome swamp (when adjacent to sheetflow or drainage features), basin

swamp (conditions same as dome swamp), freshwater tidal swamps (when associated

with freshwater drainage systems), bay swamp (same as dome swamp), prairie

hydric hammock, bottomland forest, stringer swamp

-

Non-Forested

Wetlands - wet prairie (in Peninsular Florida), basin marsh, depression

marsh (chiefly southwest Florida within range), floodplain marsh, freshwater

tidal marsh, slough marsh (in Peninsular Florida)

-

Pine

Flatwoods - wet flatwoods, cabbage palm flatwoods

-

Ponds

and Lakes - river floodplain lake, sinkhole lake

-

Sinkholes

and Outcrops - limestone outcrop

Aquatic

Milkweed Population Dynamics

Aquatic

milkweed’s niche revolves around its ability to recruit and grow in wetlands

where competition is excluded by long hydroperiods, minimal sunlight, and

flowing water.

Generally,

aquatic milkweed can be detected in any wetland community type (within its

range in Florida) where conditions exclude aggressive competition by herbaceous

and woody species, and water flow velocity is sufficient to transport aquatic

milkweed seeds to bare soil in some sort of “seed trap.”

As with many other native plant species, aquatic milkweed’s population dynamics vary between different regions within its range. Geology and hydrology present different niches across aquatic milkweed’s range. Predicting and identifying the regional differences (and similarities) in aquatic milkweed’s spatial distribution plays a significant role into the ecology and migration of monarch butterflies in the southeastern United States.

Drainage

District Population Dynamics - Floodplains

Quintessential

Drainage District Habitat: Floodplain swamps and bottomlands along riparian

corridors of rivers.

|

| Typical Floodplain Habitat Meandering Through Uplands - Washington County, Florida |

Drainage district populations typically begin within drainage headwaters where measurable flow rates originate and terminate where the respective drainage terminates, which is usually in a floodplain mouth in a coastal district. Populations occur in three types of coastal plain drainage systems – alluvial, blackwater, and spring-run systems. Asclepias perennis is absent from seepage stream systems, such as steepheads springs and acid seepage bogs in West Florida.

In riparian

districts and their associated drainage systems, occurrences of Asclepias

perennis are confined to relatively narrow, sinuous distributions that

meander through upland communities. Due to the species’ reliance on flowing

water for seed dispersal and recruitment, population expansion is limited by

the seasonal high water (SHW) elevation of the respective drainage basin. Thus,

expansion or seed dispersal into uplands occurs infrequently or never. Seedling

recruitment is typically proximal or downstream from established populations.

Seedling recruitment is virtually never upstream from source populations.

An inference gained from this information is that populations within discrete

drainage districts generally do not exchange genetic material (outcross) with

populations in adjacent drainage basins; e.g., Wakulla River and St. Marks

River populations do not engage in genetic exchange north of their confluence.

A secondary inference is that monarch and queen larval host habitats can form

distributions that mirror riparian corridors inland through upland

habitats.

Drainage

district sloughs, oxbows, and backwaters are ideal habitats for aquatic

milkweed, particularly where backflow from the associated river or creek enters

the slough. Such sites are dominated by Nyssa, Betula, Taxodium, and Planera.

Great examples exist along the Ochlockonee River. South Florida sloughs are

typically not associated with primary drainage features with high flow rates

and are generally south of the range of Asclepias perennis; thus,

sloughs are not habitat for the species in the southern-half of Florida.

Drainage

district populations are associated with “seed traps”, whereby the water-dispersed

seeds of aquatic milkweed are captured within depressional features occupied by

colonial plant species. Lizard’s tail (Saururus cernuus) serves as a

primary seed trap for A. perennis. Colonies of various Carex,

Eleocharis, Juncus, and Rhynchospora species serve as secondary seed

traps in the upper reaches and backwaters of drainage districts.

|

| Depression Within Floodplain - Lizard's Tail Milkweed Trap |

Human-derived structures also serve as seed traps Engineered

dynamics can be utilized to explain dispersal and establishment trends of Asclepias

perennis populations in engineered ditches and drains with periodic,

flowing water; e.g., Asclepias perennis populations within the Morris

Bridge Road ditches through the Hillsborough River floodplain.

As a note, culverted or bridged roads through floodplain populations can produce positive or negative impacts on aquatic milkweed populations, largely dependent upon the extent of the road design through wetland habitats. For example, Morris Bridge Road in Tampa, Florida has caused river flow to “backup along the north side of the road, thereby dispersing aquatic milkweed seeds north and south into a ditch before the water bottlenecks into the actual river course under the bridge. The consequence of this is an abnormally high density of aquatic milkweed on one side of the bridge, and a very low density on the other side.

|

| Aquatic Milkweed Population Largely Confined to Engineered Seed Traps on East Side of Bridge |

|

| Aquatic Milkweed Establishment in Culverted Ditch through the Hillsborough River Floodplain |

Drainage District Population Dynamics - Coastal Populations

Near the

terminus of a drainage system at the coast, aquatic milkweed populations occur

(and end) where floodplain swamp natural communities transition into freshwater

tidal swamps and freshwater tidal marshes. In these natural community

transitions, Asclepias perennis populations may be infrequently found in

atypical, open habitats dominated by Amphicarpum muehlenbergianum, Cladium

spp., Ludwigia repens, Sagittaria spp., and Pontederia cordata. In these

coastal, non-forested wetlands, Asclepias perennis is infrequently

sympatric with Asclepias lanceolata or Asclepias incarnata,

particularly where floodplain swamp forest transitions into floodplain marsh

and/or hydric hammock. Populations will typically be limited to ecotonal

transitions due to aggressive competition from herbaceous wetland species,

increasing salinities, and fire suppression.

|

| Coastal Rivermouth Population - Where Floodplain Forests Transition into Non-Forested Wetlands |

Basin-Platform Populations

Quintessential

Basin-Platform Habitat: Basin swamps, depression swamps and hydric hammocks

embedded within a connected, intermittent creek systems, or below the seasonal

high water (SHW) elevation in drainage basins or on karst platforms below the

SHW.

|

| Typical Basin-Platform Habitat Diffuse Across Landscape - Levy County, Florida |

|

| Basin Platform Landscape with Braided, Intermittent Streams Connecting Wetlands through Flatwoods to Primary Rivers - Southwest Florida |

|

| Aquatic Milkweed Within Seasonally Connected Slough Through Flatwood-Hydric Hammock Complex - Seasonally Connects to Myakka River |

Basin-platform (BP) population dynamics are more complicated than drainage district populations. BP populations are not confined into narrow distributions by surrounding uplands, and populations can be found in a higher diversity of habitats.

Basin-Platform

populations of Asclepias perennis occur where landscape-scale surficial

sheet flow events occur within low-lying, broad geophysical districts. Such

landscape features were formed by ancient shallow bays, seas, barrier island

accretion, and carbonate platforms. The natural communities that occur at the

surface of these features are variable, and often correlate with the elevation,

overburden of sand deposits, and proximity of limestone to the surface. The Big

Bend drowned karst district, the Green Swamp Basin, and the Peace River Basin

are examples of regions where basin-platform populations occur.

Basin-Platform

Populations – Escarpment Populations

BP populations are frequently

adjacent to or between ancient sand ridges and escarpments and can also form at

fracture points in limestone deeply seated under sand ridges. Basin populations occur on soils where subsurface

limestone strata are typically deep enough to not influence surface soil

chemistry. Subsurface limestone underlying escarpment soils are typically karst

with many voids and input/output hydrological features.

Where

surficial karst features are present at the surface, Asclepias perennis populations

occur in surficial openings within “disappearing stream” districts (e.g., the

Aucilla River), where seeds are dispersed underground via subterranean river-flow

and deposited at soil accumulations within other surficial openings

downstream).

|

| Aquatic Milkweed Population Within a Karst Window of the Subterranean Aucilla River |

Examples

include the Green Swamp Basin, San Pedro Bay, the Withlacoochee-Lake

Panasoffkee Basin, the Wekiva River Basin. Such places are dominated by

low-lying wetland natural communities and surface waters.

Basin-Platform

Populations – Platform Populations

Platform Populations tend to

be coastal and near-sea level.

Platforms

usually have limestone near the surface but lack significant karst features

such as sinkholes and major spring complexes. Hydric hammocks and wet flatwoods

dominate such areas and are connected with each other (and coastal natural

communities) via braided or anabranching creek networks. Many of these creek

systems are unnamed.

Platform

populations of aquatic milkweed - such as populations within the drowned karst

region of the Florida Big Bend - are associated with limestone seed traps

within coastal hydric hammocks, where water-dispersed seeds accumulate along

limestone features (and along wood debris or large trees) during sheet flow

events and flood stages.

|

| Aquatic Milkweed Recruitment Along a Limestone Boulder in a Surficial Limestone Seed trap |

Aquatic

Milkweed and Isolated Wetlands

The species

is not likely to be detected in herbaceous-dominated, fire-dependent wetlands, even

if water flow/velocity are sufficient for seed dispersal. At the margins

between forested and non-forested wetlands in drainage districts, aquatic

milkweed can occasionally recruit into marshes, wet prairies, graminaceous

karst plugs, edge marshes and other non-forested wetlands; the species is

otherwise absent from non-forested wetlands.

Hydroperiod,

low flow rates and fierce herbaceous competition exclude Asclepias perennis

from the majority of freshwater marsh community types. However, the species occurs

infrequently in depression marshes embedded in floodplains, hydric hammocks and

karst drainage districts (such as graminaceous karst plugs or edge marshes).

The species can also be found infrequently in non-forested wetlands within

river/creek mouths at the coast (where they transition into brackish river

marshes.

Aquatic milkweed is not present in genuinely isolated forested wetlands, even if the wetland is forested with associated canopy species. Basin swamps and isolated depression swamps (such as dome swamps) generally lack the input-output flow rates and riparian connectivity to support long-term populations of Asclepias perennis. Basin swamps, depression swamps and hydric hammocks embedded within a connected, intermittent creek system or below the SHW elevation in floodplains (as is prevalent in the Big Bend Region) are exceptions with occasional populations but are still not primary habitat due to low flow rates, isolation, and herbaceous competition.

Declining

Populations in Natural Habitat and Increasing Populations in Engineered

(Roadside) Habitat

In a 10-year

population survey of aquatic milkweed in Florida, results showed that a

majority (57%) of populations were found exclusively in ditches along the side

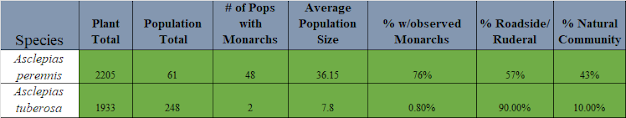

of the road, or (at a minimum) were rare in adjacent habitats.

At survey

sites where aquatic milkweed was prevalent throughout intact habitat (at 43% of

assessed site), the populations were within habitats with minimal impacts to

wetland hydrology. Data tables for this information can be found here.

|

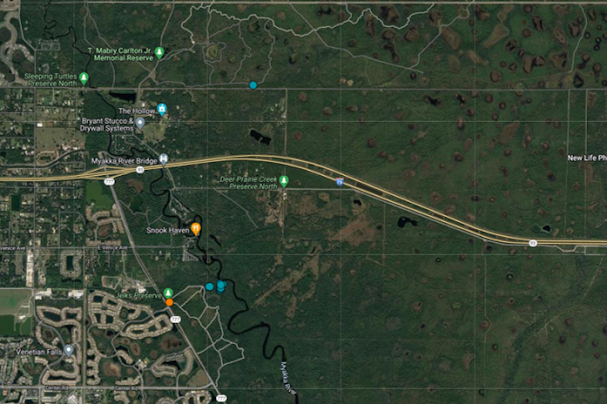

| Results of 10-Year Assessment Show Aquatic Milkweed Leaning Towards Roadsides |

It is unclear why the species has become roadside-only in many places, as the species is not dependent upon fire to maintain most of its habitat. Survey data suggests that hydrological modification to associated wetlands is strongly associated with aquatic milkweed becoming roadside only. 3 consequences of roadside ditching or bridge-building have been implicated in producing roadside populations of aquatic milkweed:

1 - Roadside

ditching lowers water levels and velocities in the adjacent wetland

2 –

Velocities become higher where water is directed into bottlenecks through

roadside ditches, culverts, or under bridges, thereby depositing seeds into these

sites instead of into downstream floodplain habitats.

3 –

Reductions in wetland water levels and soil mounding to support bridges allows for

recruitment of plant species into the margins of floodplain (except for the

lowermost reaches) that compete and exclude aquatic milkweed.

Aquatic

milkweed is found in roadside ditches that do not have suitable (adjacent)

habitat. In some surveyed populations, it was evident that suitable natural

communities had been removed during the course of private development. In other

cases, it appeared that populations were the result of waterflow in the

roadside ditches, transporting seeds away from native habitats. In this case,

the engineered ditches are acting as analogues of creeks.

Roadside populations

of aquatic milkweed in Florida, Louisiana, and Texas provide great examples of the

aforementioned dynamics.

Based on survey results of aquatic milkweed populations in healthy natural communities, it is assumed that populations that are not impacted by direct and adjacent hydrological engineering features are secure, so long as landscape scale reductions in water table or SHW levels do not occur.

Conservation

of Aquatic Milkweed in Roadside Ditches

Roadside

ditches are arguably the greatest repository of the highest numbers of plants

in many parts of their range. Significant hydrological modifications to

sheetflow and drainage are ongoing across the region, and many populations are

relegated to ditches and swales. Additionally, overwithdraw of the aquifer has

created significant reductions in hydrological output, lowering the SHW level

to lower elevations, isolating wetlands that previously incurred inputs of

water. High-magnitude springs have ceased to flow across the peninsula in the

last 50 years, and many populations may have been extirpated or relegated to nearby

ditches. Populations in drainage district habitats are generally secure.

However, basin-platform populations are declining in the peninsula due to

vanishing sheetflow events, ditching, logging, and conversion to pine

plantation or development.

Herbicide

as an Emerging Threat

In what we

refer to as the “herbicide revolution” of the 2010s, The Milkweed Foundation began

to document increasing impacts to roadside populations of aquatic milkweed due herbicide

applications. State and local agencies, and linear facility companies have

shifted into herbicide utilization (and reduced mechanical utilization) for

economic reasons, and it has become very common for broadcast applications of

herbicide to impact miles of roadside aquatic milkweed habitat. Conferring with

agencies, politicians, and power company representatives will be necessary to

prevent the extirpation of a majority of roadside aquatic milkweed populations.

.png) |

| 7/19/2023 - Largescale Herbicide Impacts to a Roadside Aquatic Milkweed Population |

Monarch

and Queen Butterfly Habitat

Aquatic

milkweed is a preferred larval host by monarch and queen butterflies. Long-term

population surveys demonstrate high rates of utilization of the species by these

insects.

In

addition to being an evergreen milkweed that provides large, year-round biomasses

of larval host material, the microclimates and native plant communities of

aquatic milkweed habitat provide preferable conditions for monarchs and queens.

Microclimates

within Aquatic Milkweed Habitats

The

moderating nature of water and the closed canopy of many types of aquatic milkweed

habitats provide opportunities for monarchs and queens to escape adverse temperature

conditions in adjacent communities and/or uplands. In the dormant season, these

habitats are warmer than the surrounding landscape, and cooler in the summer.

|

| Temperature Readings Within Aquatic Milkweed Habitat Showing Moderation from Uplands |

Abundance of Nectar Sources for Adult Butterflies

A high diversity of flowering species utilized by adult monarchs and queens is present with aquatic milkweed habitat. Notably, numerous species and genera provide flower nectar resources in the dormant season. The following is a list of wildflower species that monarchs have been observed utilizing in aquatic milkweed habitat:

|

Binomial |

Common Name |

Winter Resource |

Notes |

|

Acer rubrum |

red maple |

Yes |

Important Resource in Jan/Feb |

|

Baccharis glomeruliflora |

silverling |

Yes |

Important Resource in Jan/Feb |

|

Bidens alba |

beggarticks |

Yes |

Important Resource in Jan/Feb |

|

Bidens mitis |

smallfruit beggarticks |

Yes |

Important Resource in Jan/Feb |

|

Clematis spp. |

pine hyacinth |

Yes |

Important Resource in Jan/Feb; Notably C. baldwinii & C.

crispa |

|

Crataegus

spp.

|

all hawthorne species |

Yes |

|

|

Ditrysinia fruticosa |

gulf Sebastian-bush |

No |

|

|

Eupatorium perfoliatum |

rough boneset |

No |

|

|

Eutrochium fistulosum |

Joepyeweed |

No |

|

|

Helianthus

agrestis |

southeastern sunflower |

Yes |

|

|

Helianthus angustifolius |

narrowleaf sunflower |

Yes |

|

|

Iris spp |

all iris species |

Yes |

Notably I. savannarum |

|

Justicia americana |

American waterwillow |

No |

|

|

Justicia angusta Justicia ovata |

looseflower waterwillow |

Yes |

|

|

Melanthera

nivea |

snow squarestem |

Yes |

|

|

Lobelia cardinalis |

cardinalflower |

No |

|

|

Lonicera sempervirens |

coral honeysuckle |

No |

|

|

Packera glabella |

butterweed |

Yes |

Important Resource in Jan/Feb |

|

Physostegia

spp. |

all dragonhead species |

Yes |

|

|

Rubus spp |

all blackberry species |

Yes |

Important Resource in Jan/Feb |

|

Saururus cernuus |

lizard’s tail |

Yes |

|

|

Smallanthus uvedalia |

bearsfoot |

No |

|

|

Solidago fistulosa |

pinebarren goldenrod |

No |

|

|

Solidago rugosa |

wrinkleleaf goldenrod |

Yes |

|

|

Symphiotrichum spp |

new world asters |

Yes |

Important Resource in Jan/Feb in Peninsula |

|

Viburnum obovatum |

Walter’s viburnum |

Yes |

Important Resource in Jan/Feb |

|

Viola spp. |

all violets |

Yes |

Important Resource in Jan/Feb |

Generalizations About the Relationship Between Aquatic Milkweed and

Monarch Butterflies

-

At

least in the coastal plain, moderate conditions and evergreen aquatic milkweed

allow for potential year-round occupancy of monarch butterlies.

-

Aquatic

milkweed facilitates year-round occupancy north of temp zone 9 in Florida, with

non-migratory reproduction being documented statewide, year-round.

-

Coastal

hibernaculums for monarchs facilitated by moderated temperatures coincide

geographically with abundant aquatic milkweed habitat and large biomasses of

native milkweed.

-

Monarch

preference for aquatic milkweed is demonstrable.

-

Cultivation

of tropical milkweed should be discouraged, but not on the basis of its

evergreen nature.

-

Aquatic

milkweed populations are large and stable in communities with no hydrological

impairments; but are increasingly shifting towards roadside dominance due to

widespread water flow manipulation and/or flood control.

Comments

Post a Comment

We will respond to your comment shortly. Thank you!